SARS-CoV-2 Trends: Recent Variants, What’s to Come, and What’s Still Needed

Almost a year after the initial onset of COVID-19, new variants of SARS-CoV-2 emerged, spreading quickly and straining health systems globally. What can we learn from those variants and how can health system leaders gain insights into what’s to come in order to prepare their communities?

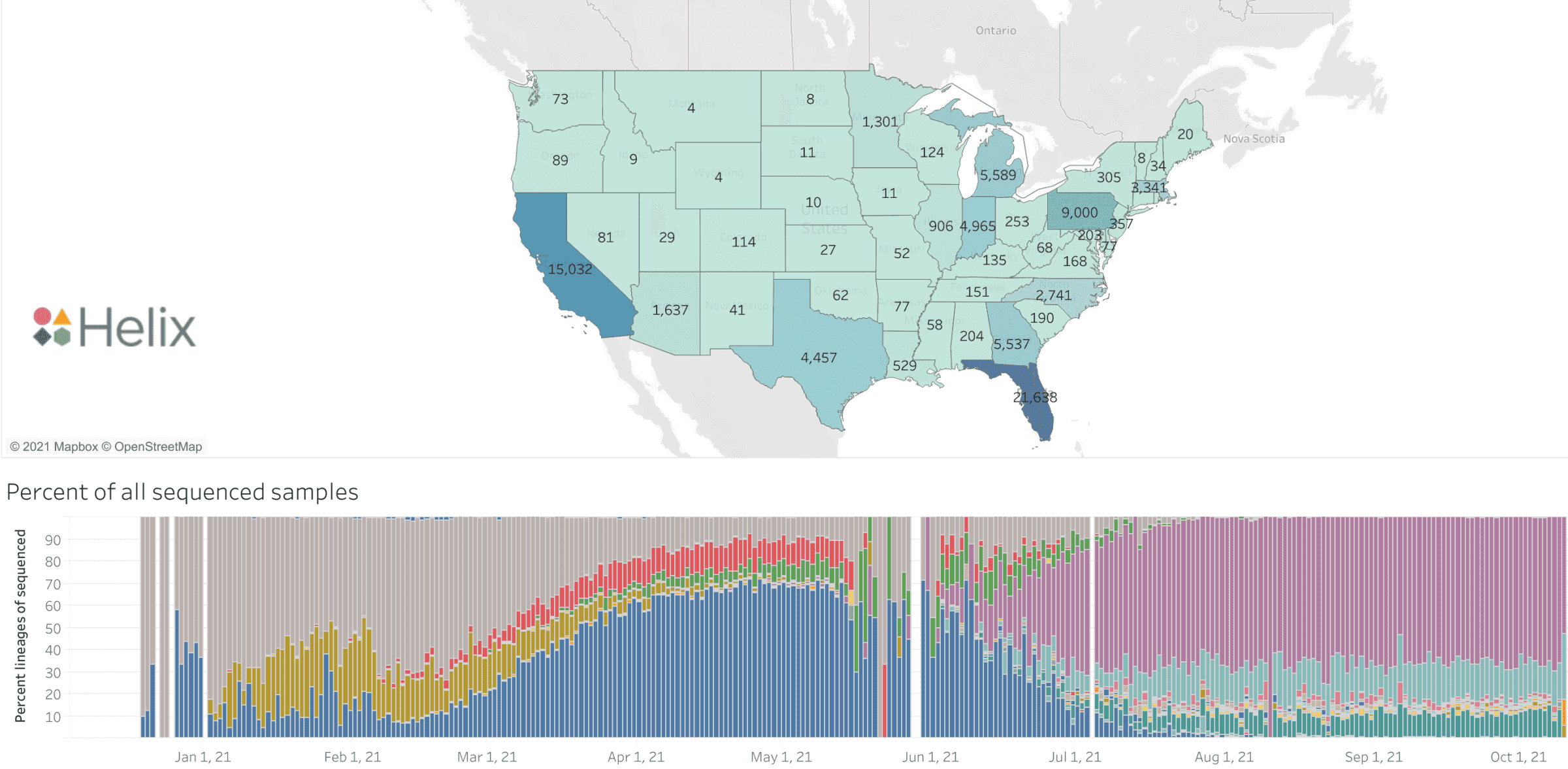

Active viral surveillance is a critical part of the answer as it offers the opportunity to stay ahead of new variants and curb outbreaks before they begin. As a nationwide viral surveillance organization that has generated tens of thousands of viral sequences for ongoing research, our scientists were among the first to detect and predict the spread of the Alpha and Delta variants in the US. Their continued diligence in tracking variant trends illuminates a lot on how the pandemic has unfolded, what we anticipate in the near term and what’s still needed for health system leaders to best prepare for the future.

The Mu variant was likely more transmissible than the Alpha variant, but was outcompeted by Delta

Worldwide prevalence of the Mu variant over time. Image taken from Outbreak.info on October 26, 2021

In January, 2021, officials in Colombia reported detection of a variant that would come to be known as the Mu variant (B.1.621)2. Mu would eventually make its way into several countries, including the US3. Our scientists saw Mu begin to rise in prevalence starting in late May. It quickly reached ~10% prevalence in Florida, but then decreased to essentially zero.

Worldwide, the Mu variant reached a height of only 0.8-1.2% prevalence in late June3. During its rise, the Alpha variant was dominant in the United States. The quick spike in prevalence in Florida suggests that this strain’s collection of variants likely gave it better transmissibility relative to the Alpha strain, and was on track to displace it.z

But it didn’t play out that way. When Mu grew to its height in Florida, Delta was not yet dominant, only representing about 50% of cases in the US. But as Delta spread, Mu began to decrease. While it seemed to have a small advantage against Alpha, it was proving to be a lot less transmissible. And as of October, Helix scientists have not seen Mu again in our samples.

Variant R.1 was even less likely than Mu to spread

Worldwide prevalence of the R.1 variant over time. Image taken from Outbreak.info on October 26, 2021

A recent wave of news reported the appearance of the R.1 variant. While many headlines warned of its potential rise, data suggests that it was never a prevalent strain except for in a few, very small geographical locations. Globally, approximately 10,000 cases of R.1 have been reported, with a peak number of cases coming in April, 20213. The limited spread has kept it from being classified as a variant of concern or a variant of interest by the World Health Organization (WHO).

Helix’s viral surveillance dashboard reflected this trend. R.1 rose to about 1-2% in segments of the country in March but didn’t last long. There were enough cases that if it was going to be a breakthrough variant, it would have exploded in numbers but it has all but disappeared in our data since April.

Unlike Mu, R.1 appeared at a time before Delta had fully emerged, meaning it’s unlikely that R.1 disappeared in response to the spread of Delta. Instead, it’s more likely that R.1 was not competitive, and it spread in pockets where other variants hadn’t yet reached. While it’s hard to say what happened, timing suggests that it might have been outcompeted by Alpha.

New variants are likely to be evolutions of the Delta variant

The Delta variant has been extremely effective at spreading around the world, with more than 1.5 million cases reported across 171 countries. Through a mixture of mutations, the Delta variant has become nearly 40% more transmissive than the Alpha variant4.

To address the spread of this virus, much of the world has begun large vaccination campaigns. For these vaccines to be effective, the fragments they present to the immune system need to closely resemble parts of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which may change in subtle ways with each variant. So far, our vaccines have been effective against all known variants. However, the threat of one breaking through is concerning for many researchers and healthcare providers.

The Delta variant has spread enough that it has many opportunities to evolve, meaning that future variants are likely to be derived from Delta. At the moment, the variant classification database reports 111 recognized varieties.

AY.4.2 is being closely monitored but is not yet of concern

One of those varieties of Delta that has recently drawn the world’s attention is AY.4.2. In the beginning of October, this variant appears to have risen in prevalence among cases in the United Kingdom, growing from 4% of SARS-CoV-2 positive cases in mid-September to 6% of cases in the first week of October. This rise has prompted officials in the UK to classify AY.4.2 as a variant of interest to be closely monitored.

Our scientists did not find any AY.4.2 until October 9, 2021 and have since observed two samples containing this variant. Due to its rarity, most US experts are not too concerned about AY.4.2 but agree that it’s worth monitoring and investigating.

A collaborative network of surveillance laboratories is key to public health

Whether or not one of these future variants will lead to outbreaks will depend on our ability to detect new ones as they arise and implement rapid, targeted public health response measures.

Because public health departments have been historically underfunded, industry and academic laboratories are critical in this effort because these facilities have the instruments, machines, reagents and workforce needed to quickly and effectively respond to potentially large-scale outbreaks while also supporting ongoing surveillance.

Helix’s viral surveillance dashboard can help with local forecasting as it allows researchers and the general public to observe sequencing trends nationally and by state. But a robust collaborative surveillance effort is still needed, one in which health systems are connected to allow for rapid information sharing. Such a network would enable rapid deployment of preventative measures in response to outbreaks before they overstrain our communities.

References

1. Galloway, Summer E. “Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 Lineage — United States, December 29, 2020–January 12, 2021.” MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, vol. 70, no. 3, 2021, http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7003e2.htm?s_cid=mm7003e2_w,

2. “Mu COVID Variant: All You Need to Know about the New UK Coronavirus Strain.” BBC Science Focus Magazine, http://www.sciencefocus.com/news/mu-covid-variant/. Accessed 27 Oct. 2021.

3. “Outbreak.info.” Outbreak.info, outbreak.info/. Accessed 27 Oct. 2021.

4. Callaway, Ewen. “The Mutation That Helps Delta Spread like Wildfire.” Nature, 20 Aug. 2021, 10.1038/d41586-021-02275-2. Accessed 23 Aug. 2021.

Categories