Technical Briefing 5: SARS-CoV-2 Antiviral Treatment Gaps

Executive summary

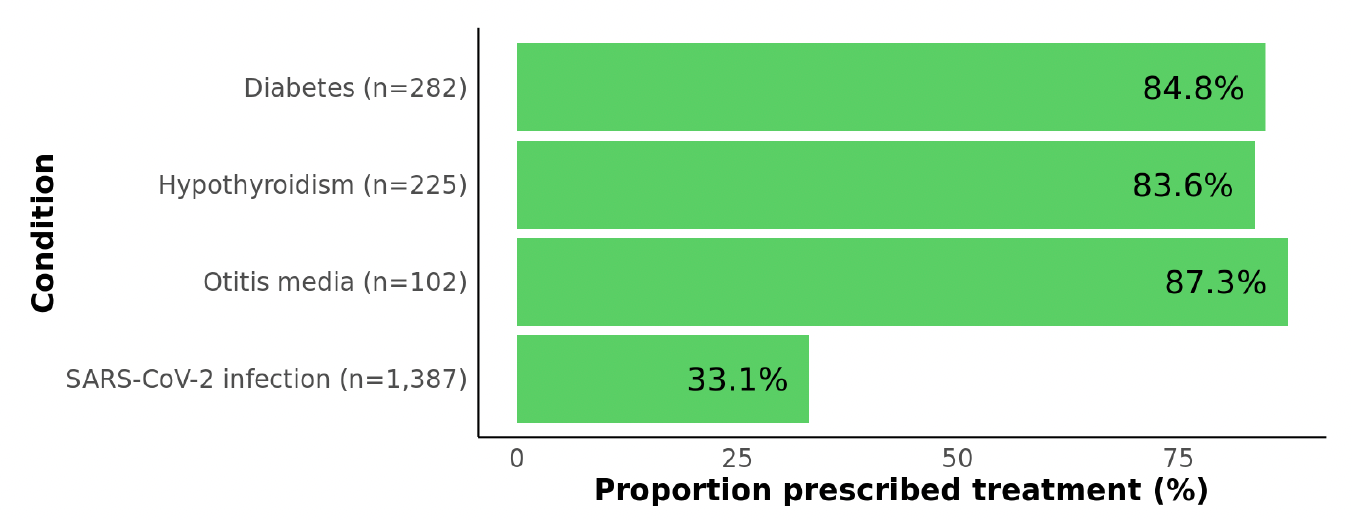

- Among 1,387 non-hospitalized adult SARS-CoV-2 patients at risk for progressing to severe disease, only 33% were prescribed a SARS-CoV-2 antiviral as part of clinical care, which was substantially lower than the 84-87% prescribed standard-of-care treatment for each of three different control conditions unrelated to SARS-CoV-2.

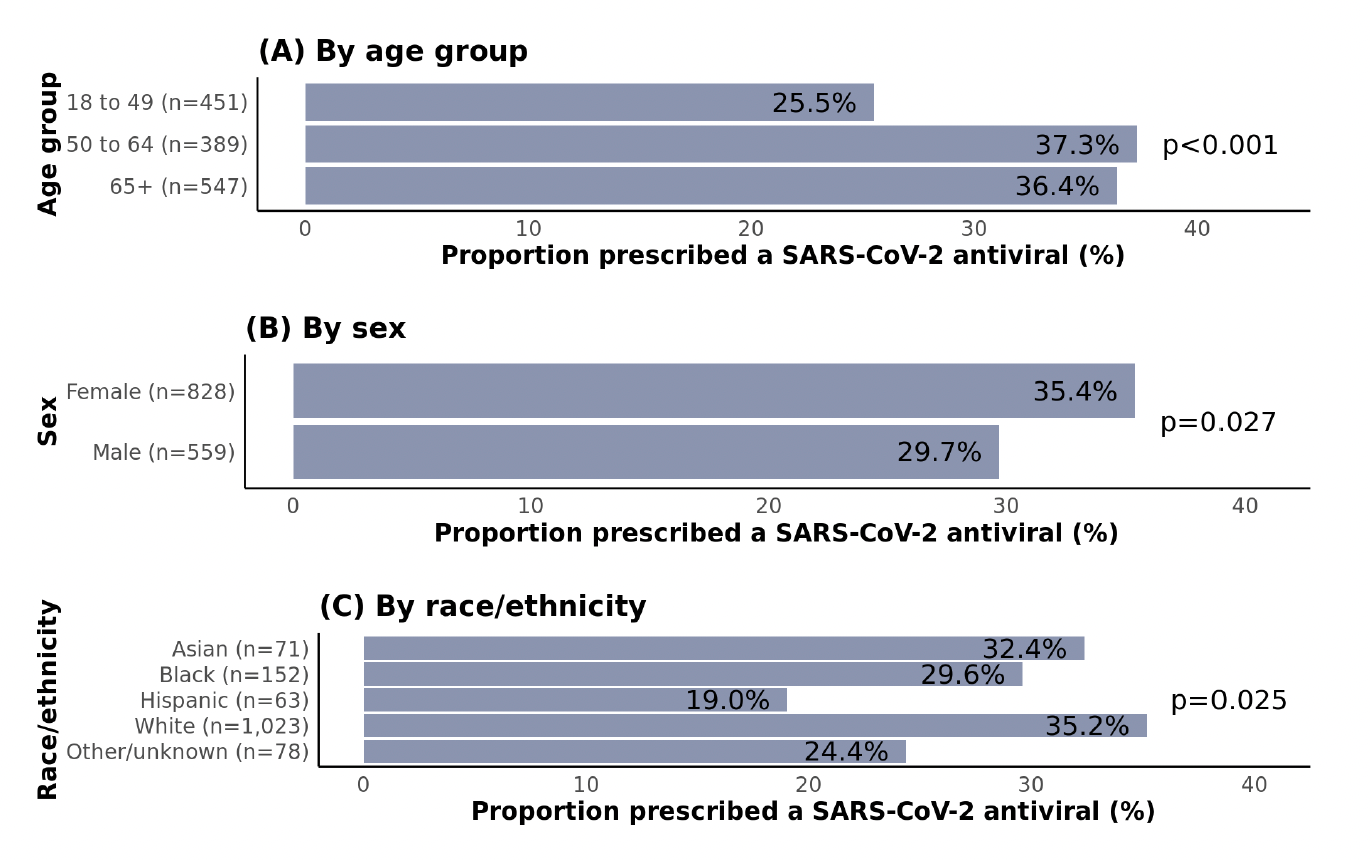

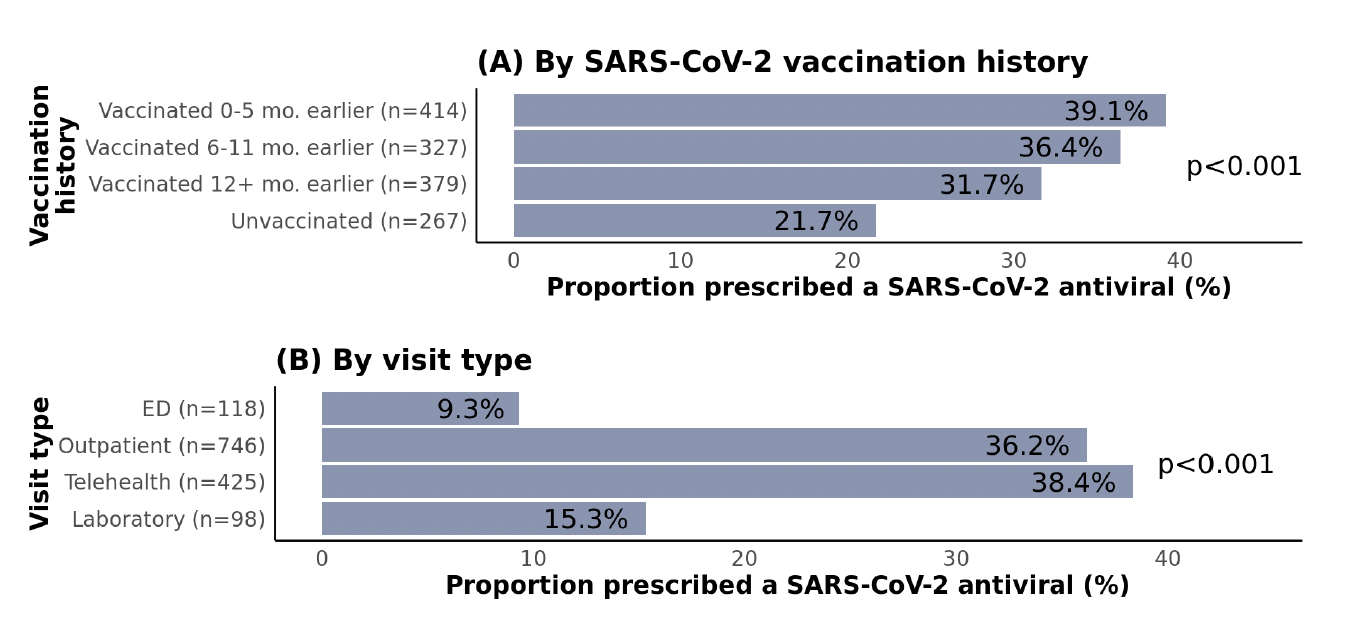

- Antiviral prescription rates were higher among patients aged 50-64 and ≥65 (vs. 18-49) and lower among patients who were male (vs. female), Hispanic (vs. non-Hispanic white), unvaccinated (vs. vaccinated), and seen in emergency department (ED) or laboratory-only (vs. outpatient) healthcare settings.

- There is a critical need to address this large antiviral treatment gap by identifying and eliminating barriers to treating eligible high-risk patients in non-inpatient settings. 1,387 non-hospitalized adult SARS-CoV-2 patients at risk for progressing to severe disease, only 33% were prescribed a SARS-CoV-2 antiviral as part of clinical care, which was substantially lower than the 84-87% prescribed standard-of-care treatment for each of three different control conditions unrelated to SARS-CoV-2.

Background

SARS-CoV-2 antiviral agents are an important treatment option for preventing severe COVID-19. The CDC recommends the oral antiviral nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid; ages ≥12 years) and the intravenously administered antiviral remdesivir (Veklury) as the preferred treatments for mild-to-moderate COVID-19 in non-hospitalized patients with risk factors for progression to severe COVID-19. In practice, remdesivir is more commonly used to treat severe COVID-19 in hospitalized patients, as its intravenous administration limits its use in outpatient settings. For patients in whom nirmatrelvir/ritonavir is contraindicated due to possible drug-drug interactions, molnupiravir (Lagevrio; ages ≥18 years) is a safe alternative oral antiviral agent.

Leveraging data from health systems, we examined SARS-CoV-2 antiviral prescribing patterns in 2023 with respect to a broad range of patient demographic and clinical factors including SARS-CoV-2 vaccination history, type of visit, specific acute respiratory diagnoses, and a range of high-risk underlying conditions. The objective of this analysis was to evaluate gaps in the prescribing of SARS-CoV-2 antiviral agents in a real-world cohort of non-hospitalized SARS-CoV-2-infected adults at high risk for progression to severe disease.

Data source

Helix receives residual clinical samples for patients with a positive diagnostic respiratory virus test result from a network of healthcare systems, located in the US northwest, south, and midwest regions, under an IRB-approved research protocol. In addition to receiving samples, Helix receives a limited set of associated patient electronic health record (EHR) data. EHR data elements collected include demographics, medical visits, diagnoses, drug prescriptions/administrations, and vaccine records (linked with state vaccine registries). Helix maintains certain patient data for purposes of facilitating public health reporting. Data used for research is de-identified in accordance with HIPAA’s Expert Determination method.

The analytic cohort was selected from 1,674 non-hospitalized adult patients with a positive SARS-CoV-2 test result between February 28-June 23, 2023. Of the 1,674 patients, 1,396 (83%) had at least one risk factor for progression to severe disease (941 aged ≥50 years, 268 unvaccinated, and 1,013 with one or more high-risk conditions). Of those patients, 1,387 (>99%) met all other inclusion criteria and were included in this analysis (see Data Processing).

Overall prescription rate in high-risk SARS-CoV-2 patients

Overall, 33% (459) of non-hospitalized adults were prescribed (or administered) a SARS-CoV-2 antiviral within 5 days of SARS-CoV-2 testing. The most common antiviral prescribed was nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (408, 89%), followed by molnupiravir (48, 10%) and remdesivir (4, 1%).

To put the antiviral prescription rate in perspective and ensure availability of medication records (in general), we created three internal control groups, each with a different underlying condition (comorbidity unrelated to SARS-CoV-2 infection) for which we would generally expect patients to be treated. The conditions examined were diabetes mellitus type 2, hypothyroidism, and otitis media (ear infection; among patients ≤6 years old).

Figure 1: Proportions of patients with each of three control conditions and with SARS-CoV-2 infection who were prescribed a standard-of-care treatment. For each control condition, we evaluated whether at least one medication record consistent with treatment was present: diabetes medication (e.g., metformin, insulin), levothyroxine to treat hypothyroidism, or antibiotic (e.g., amoxicillin) to treat otitis media (within 14 days of otitis media diagnosis).

As depicted in Figure 1, coverage of medications to treat each of the control conditions was consistently high, ranging from 84-87%. In contrast, the 33% prescription rate in high-risk SARS-CoV-2 patients is startlingly low, albeit an improvement over the 18% of eligible SARS-CoV-2 patients who received oral antiviral treatment in mid-2022. In that study, reported reasons for not receiving treatment included having minimal symptoms, not thinking treatment was needed, and not receiving a healthcare provider’s recommendation. Despite antivirals being a proven tool to prevent severe COVID-19, clinicians may not prioritize treatment due to the lower number of hospitalizations and deaths compared with earlier in the pandemic.

Prescription rates stratified by demographic characteristics

As expected, patients aged ≥50 years were more likely to receive an antiviral than those aged 18-49 years, yet the proportion was only 36-37% in both 50-64 and ≥65 age groups (Figure 2). Females were more likely to be treated than males, and non-Hispanic white patients were most likely to receive treatment compared with racial and ethnic minorities; in pairwise comparisons, this difference was only statistically significant for Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic white patients (p=0.011). In 2022, two national EHR studies (PCORnet and Cosmos) found that Hispanic as well as Black patients were less likely to receive antiviral treatment than non-Hispanic white patients. Contributing factors may include social-structural barriers such as limited knowledge of treatment options, language barriers, medical mistrust, lower willingness to take medications, lower utilization of telemedicine services, and implicit biases among providers.

Prescription rates stratified by vaccination history and visit type

Regarding SARS-CoV-2 vaccination history, unvaccinated patients were the least likely to be prescribed treatment (Figure 3), which is inconsistent with CDC recommendations. This pattern could potentially be linked to a general tendency toward reduced health-seeking behaviors and lower acceptance of pharmaceutical interventions in patients who have not been vaccinated. Patients admitted to the ED and those with laboratory-only visits were less likely to be prescribed treatment compared with those seen in outpatient or telehealth settings.

Prescription rates stratified by high-risk condition

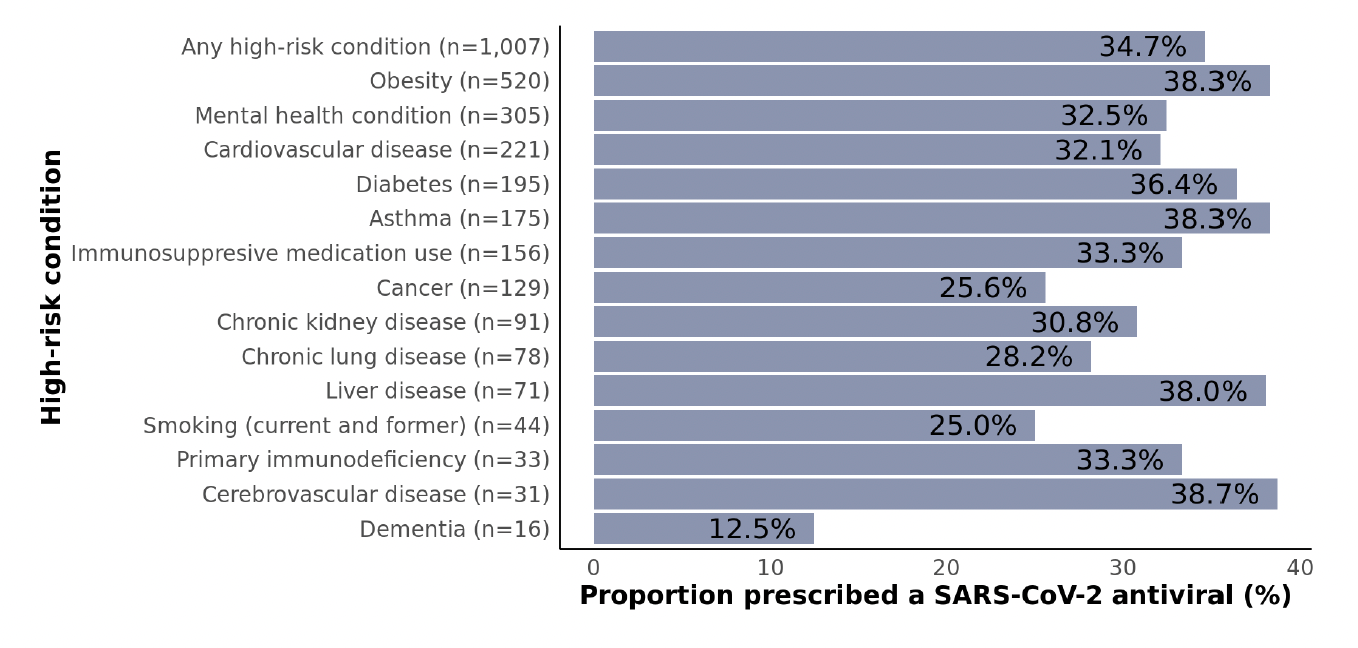

Figure 4: Proportions of non-hospitalized adult SARS-CoV-2 patients who were prescribed a SARS-CoV-2 antiviral stratified by high-risk condition subgroups. Data are not shown for subgroups with fewer than 10 patients including developmental/intellectual disability, HIV, and solid organ/stem cell transplant. Subgroups are not mutually exclusive.

Proportions prescribed treatment were not particularly different across subgroups defined by the presence of high-risk underlying conditions (Figure 4), which suggests that providers did not weigh specific conditions more heavily than others as part of treatment decisions. Overall, 35% of patients with ≥1 underlying condition were prescribed an antiviral. Among subgroups with at least 50 patients (i.e., the more common conditions), proportions ranged from 26% for cancer to 38% for obesity, asthma, and liver disease. Even when restricting the sample to patients aged ≥65 years with ≥1 high-risk condition (401), the prescription rate was still only 35% (not shown).

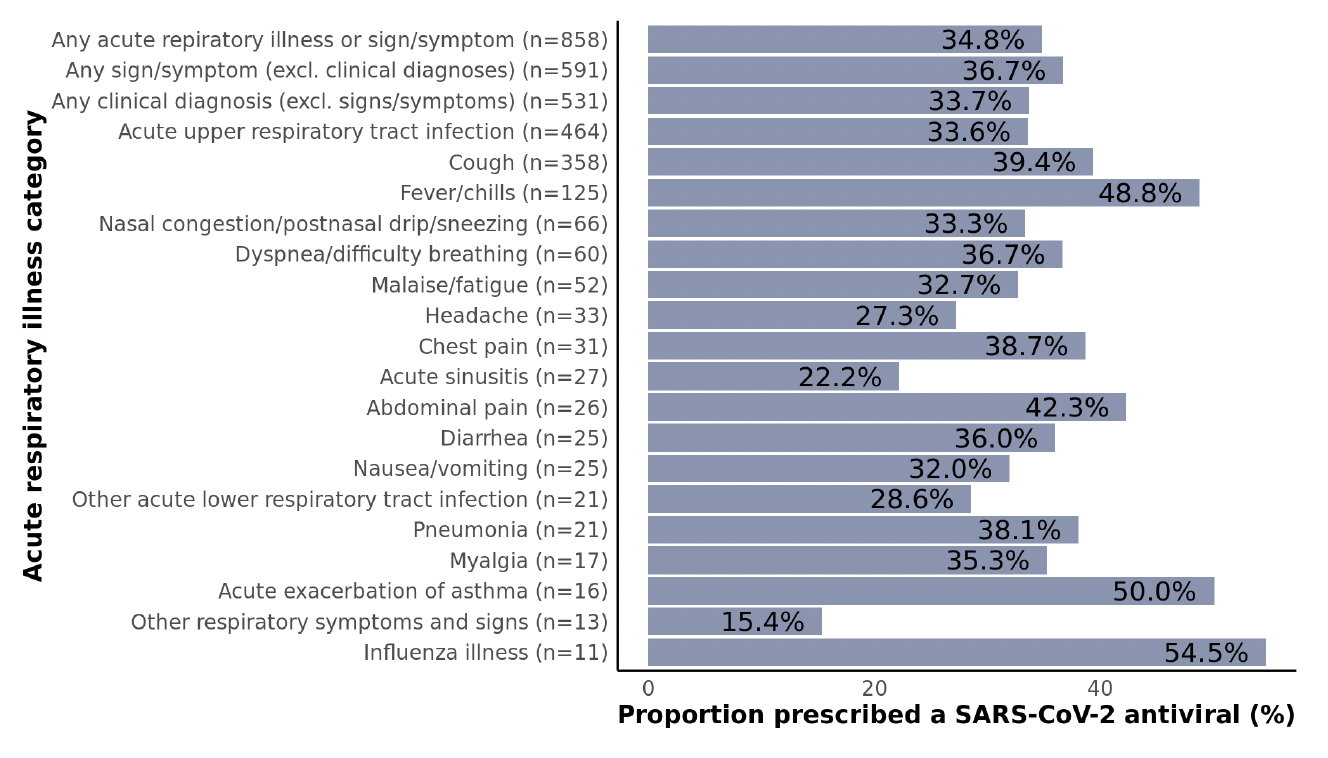

Prescription rates stratified by documented acute respiratory illness

Figure 5: Proportions of non-hospitalized adult SARS-CoV-2 patients who were prescribed a SARS-CoV-2 antiviral stratified by acute respiratory illness diagnosis subgroups. Clinical diagnoses included acute asthma exacerbation, acute chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbation, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), acute respiratory tract infection, acute sinusitis, influenza illness, other acute lower respiratory tract infection, pneumonia, and respiratory failure. All other conditions were classified as signs or symptoms. Data are not shown for subgroups with fewer than 10 patients including abnormal sputum, acute COPD exacerbation, ARDS, altered mental state/level of consciousness, asphyxia/hypoxemia, disturbance of smell/taste, ear pain, hemoptysis, pleurisy, rash, respiratory arrest, respiratory failure, sepsis, and throat pain/difficulty swallowing.

While there is some variation across respiratory illness categories (particularly for smaller subgroups), no major patterns emerged (Figure 5). Treatment rates were similar among patients irrespective of the presence of a clinical diagnosis (34%), signs/symptoms only (without a clinical diagnosis; 37%), or neither (30%) (p=0.14; not shown). It is particularly concerning that even among high-risk patients with fever/chills, only 49% were prescribed an antiviral.

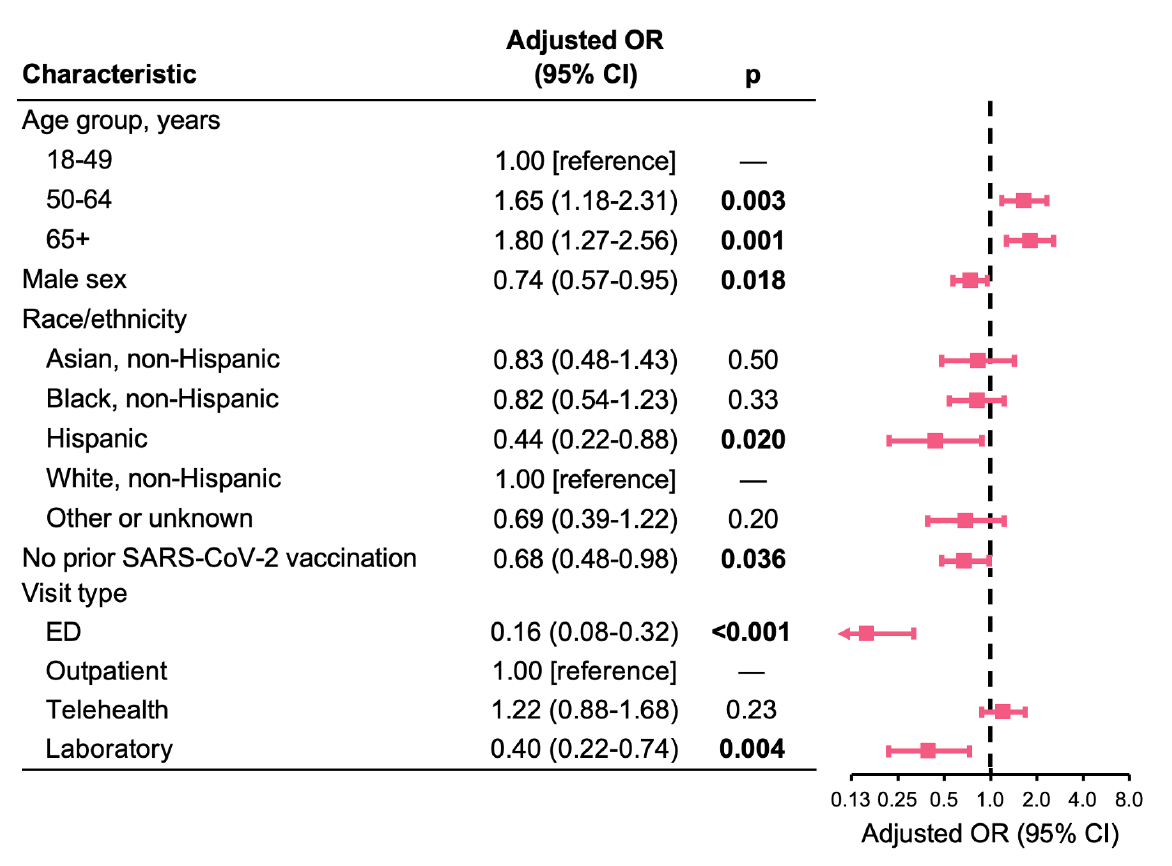

Factors associated with receipt of antiviral prescription

Figure 6: Adjusted associations of demographic and clinical factors with receipt of a SARS-CoV-2 antiviral prescription. Analyses were adjusted for specimen date (cubic spline), presence of a nirmatrelvir/ritonavir contraindication (based on medication records in the prior month), acute respiratory illness diagnosis category (clinical diagnosis, signs/symptoms only, or neither), presence of specific high-risk underlying conditions (asthma, chronic lung disease, cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, dementia, diabetes type 1 and 2, obesity, cancer, chronic kidney disease, liver disease, mental health disorder, primary immunodeficiency, immunosuppressive medication use, and ever smoking status), and all variables shown. OR indicates odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

In multivariable analysis, ages 50-64 and ≥65 (vs. 18-49) remained significantly associated with a greater likelihood of receiving an antiviral prescription (Figure 6). Male sex, Hispanic ethnicity (vs. non-Hispanic white), no prior SARS-CoV-2 vaccination (vs. vaccinated), and ED and laboratory-only visits (vs. outpatient visits) remained significantly associated with a lower likelihood of receiving an antiviral prescription (Figure 6).

Caveats

Findings should be interpreted within the context of several limitations. First, antiviral treatment was primarily based on prescription data and it is possible that prescriptions were not filled or treatment not completed. Second, it is also possible that patients received a prescription elsewhere (e.g., different health system), although it is generally expected that treatment would be prescribed by the same provider(s) who ordered SARS-CoV-2 testing. Third, information on acute respiratory illness and signs/symptoms may not be complete based on diagnosis codes alone; other free-text data in the EHR was not available for analysis.

Data Processing

The following inclusion criteria were used for this analysis: (1) aged ≥18 years; (2) infected with SARS-CoV-2; (3) not hospitalized within 1-14 days before the specimen collection date or on the specimen collection date, nor on the day immediately following the specimen collection date (to allow sufficient time for antiviral prescribing after receipt of test results); (4) had at least one risk factor for progression to severe COVID-19 disease, including ages ≥50 years, no prior SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, and/or having at least one high-risk underlying condition documented in the prior two years, including asthma, cancer, cerebrovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic lung disease, diabetes mellitus type 1 or 2, developmental or intellectual disability, cardiovascular disease, HIV, mental health condition (mood or psychotic disorder), dementia, obesity, primary immunodeficiency, smoking (current and former), solid organ or blood stem cell transplantation, or use of corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive medications (in the prior six months); (5) did not have a prior positive SARS-CoV-2 test result within 1-27 days before the specimen collection date, which would indicate that the index infection is an ongoing previously identified infection; and (6) did not have a prescription for a SARS-CoV-2 antiviral 6-14 days before the specimen collection date, which might suggest that an initial earlier positive SARS-CoV-2 test result was not available (e.g., testing elsewhere).

The outcome measure for this analysis was a dichotomous variable for whether the patient was prescribed a SARS-CoV-2 antiviral within 5 days after (or before) the specimen collection date. Since the precise date of symptom onset was not known, a window of +/-5 days was used.

Patients were included regardless of whether ≥1 acute respiratory clinical diagnosis or sign/symptom was documented because the health system’s testing policy during this time was to only test symptomatic patients. Our assumption is that patients without a documented diagnosis are likely to have had undocumented mild-to-moderate symptoms.

Prepared by Matt Levy and Shishi Luo. Special thanks to Evanette Burrows for collecting and preparing the data. Technical advisors: Pamala Pawloski and Phillip Heaton of HealthPartners.

© Helix, Inc. 2023. All rights reserved.

Helix and the Helix logo are registered trademarks of Helix, Inc.

Categories